by Jacob Dayon

Jacob Dayon is an Asian Studies major from Westfield, NJ who wrote this essay in Catherine Mintler’s Spring 2019 “Citizens” course.

“Congress shall make no law respecting an establishment of religion, or prohibiting the free exercise thereof.” – 1st Amendment of the United States Constitution

The very first line of the 1st Amendment of the Constitution allows US citizens to practice any religion they please by separating the Church and State into two separate entities. Yet even with this highly praised provision in the highest law of the land, all religions are still not created equal. What if I told you that your religion was defined not by your spiritual beliefs, but by your race, the language you speak and the clothing you wear? This has been the harsh reality of the Muslim American throughout the history of the United States.

However, on the morning of September 11th, 2001, an even darker chapter of the Muslim and Arab story in America began. Osama Bin Laden, leader of the terrorist regime Al-Qaeda who was responsible for the attacks of 9/11, expressed that he and his men were serving Muhammad, the Prophet of the god Allah, االله, in the Islamic religion. In an interview on December 26, 2001 with Al-Jazeera, a famous Arab news station, Bin Laden praises the hijackers’ actions on September 11th. He stated that “it was nineteen post-secondary students—I beg God Almighty to accept them—who shook America’s throne, struck its economy right in the heart, and dealt the biggest military power a mighty blow, by the grace of God Almighty” (Lawrence 149). He proclaims the attacks of 9/11 were executed in the name of Muhammad, Allah, and the Islamic faith. Bin Laden’s statements reflect the mentality of extremists and how they manipulate their religion in order to justify evil acts of cruelty and violence. The acts of terrorists, such as Osama Bin Laden, who claim to live their lives through Islamic principles overshadow the true meaning of the religion. Osama Bin Laden’s connections with terrorism and his outspoken devotion to Allah have caused the people of the United States to vilify the practice of Islam, and to associate its followers with terrorism since the attacks of September 11th.

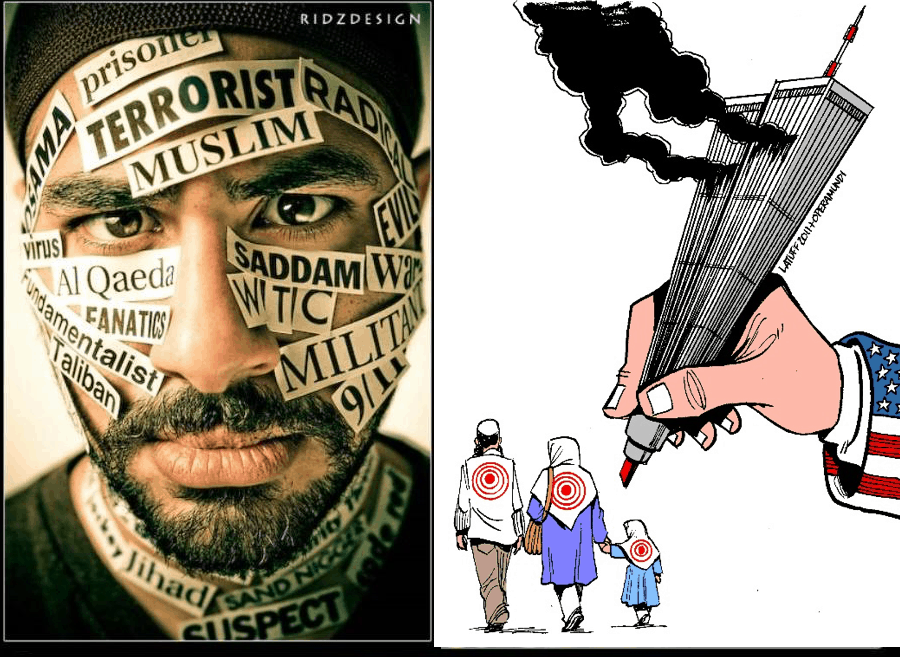

Yet, 9/11 not only subjected the Islamic religion and its believers to scrutiny, but extended these stereotypes on the basis of race. In his photograph entitled “Islamophobia,” creative director and photographer Ridwan Adhami captures an ordinary Arab man with various labels covering his face and neck which read terrorist, 9/11, Al Qaeda, Osama, Muslim, etc. (Adhami).

The skin color of the man expresses how the stereotypes created towards Muslim Americans and Arab Americans following 9/11 are not solely based upon religion, but bear racial implications as well. Since Osama Bin Laden and his hijackers were Arab natives, the American people have come to believe that all citizens with a ‘brown’ and darker skin color are Muslim, and therefore a terrorist. Currently, innocent Muslim Americans and Arab Americans cannot wear a hijab, read the Qur’an or even speak the Arabic language in public without receiving backlash and hate from their American brethren. While there are many factors and contributors to the racialization process, it is ultimately the American public who denies Muslim Americans and Arab Americans their rights as citizens of the United States through the creation and enforcement of stereotypes that conjoin Islam with Arab ethnicity.

Despite there being distinctions between Muslims and Arabs, the racialization of Islam takes the two separate identities and combines them into a single category of Muslim and Arab Americans. Before we go on to see how the Islamic religion was racialized following the attacks of September 11th, we must first understand the distinction between a Muslim American and an Arab American. A Muslim is someone who practices the Islamic religion, while an Arab is a person whose heritage or ancestry originates from areas of the Middle East and or North Africa. There is a clear distinction between the two identities as one identifies with a particular religion while the other associates with a specific geographical region. Esteemed legal scholar Hilal Elver explains that being Muslim does not equate to Arab descent. She articulates that a “majority of Arabs and Middle Easterners in the United States are not Muslims but Christians. Moreover, most Muslim Americans in the United States are not Arabs” (Elver 124). While religion and ethnicity can sometimes coincide with each other, there are explicit differences between the two identities. There are a number of Muslims that do not possess Arab ethnicity, and many Arabs in the Middle East are not Muslim. However, the Islamic religion has been racialized since the American people have associated Muslim Americans with the racial characteristics of an Arab American. The racialization process reveals how not all religions are created equal in the eyes of the American public. When I attend my Catholic church on Sunday afternoons, I see the pews filled with people of various races and ethnicities ranging from Caucasian to African American, Hispanic and Asian descent. While we all practice the Catholic religion, it would be completely ignorant to say that we are all the same. Yet, the racialization of Islam combines the two profoundly different identities causing both Muslims and Arabs in the United States to be “othered” by the American public and treated accordingly.

This othering of Muslim Americans and Arab Americans originates from the concept of essentialism, and initiates the racialization process. Essentialism is “the view that categories of people, such as women and men, or heterosexuals and homosexuals, or members of ethnic groups, have intrinsically different and characteristic natures or dispositions” (“Oxford Dictionaries”). To the typical American citizen, Muslims and Arabs are not perceived to fit the normal model of an American due to their distinct religious and cultural practices, as well as their physical appearance. Many American citizens generate assumptions about the character and loyalty of Muslim Americans and Arab Americans since they possess spiritual beliefs and a skin complexion different from their own. These common perceptions regarding Muslim culture and Arab race created a narrative where people who either practiced the Islamic religion or appeared to have Arab ancestry were labeled as “other” and “foreign.” Michelle D. Byng, an associate professor at the University of Temple, states that at the heart of essentialism is “the idea that people marked by the identity in question are genetically different from other human groups and must be treated as such” (Byng 664).

Essentialism set the platform for the two minority groups to be portrayed as terrorists following the events of September 11th. Once the attacks of 9/11 occurred, this preexisting essential label attached to Muslim and Arab Americans alike enabled both groups to be vilified by the American public. Hilal Elver depicts the idea that “the foreign culture of Muslims as sometimes ‘uncivilized’” inevitably created “the post 9/11 political environment by using the state’s responsibility to protect American citizens from ‘terrorism’” (Elver 122). The essentialist philosophy expressed toward Muslims and Arabs transitioned from a process of othering the ethnic groups to labeling them as terrorists. The American public’s fear of Osama Bin Laden and terrorist regimes led to the portrayal of Muslims and Arabs as violent terrorists, and initiated the racialization of the Islamic religion within the United States. Since the terrorists who performed the devastating attacks on the World Trade Center and the Pentagon identified with this minority group known as Muslims, innocent Muslim Americans and Arab Americans were therefore falsely associated with such violent acts. This narrative that all Muslims and Arabs are possible terrorists has made these two groups indistinguishable in the eyes of the American public.

Not only has the racialization of Islam caused Muslim Americans and Arab Americans to be seen as a threat, it also has weakened their citizenship by being forced to constantly validate their allegiance to the United States to their fellow citizens. Sociologist Saher Selod and law professor Leti Volpp express how the hysteria and fear created by the events of 9/11 have forced Muslim Americans and Arab Americans to show they are wholeheartedly loyal to the United States. In “Citizenship Denied: The Racialization of Muslim American Men and Women Post-9/11,” Selod analyzes how ordinary citizens deprive Muslim Americans and Arab Americans of the privileges of citizenship through the racialization process. She explains how private citizens serve as the “gatekeepers to citizenship” by “repetitively contesting [Muslim Americans’] status as Americans” which prevents them from obtaining “social citizenship” rights (Selod 78). Since Muslim Americans and Arab Americans are not perceived to be true Americans by their fellow citizens, they are held to a different social criterion in order to claim the American identity. These standards enforced by private citizens downgrade the value of Muslim and Arab citizenship. Like Saher Selod, Leti Volp examines the struggles that Muslim Americans face in regards to validating and receiving the rights of American citizenship. Volpp describes how Muslims possess a “weaker citizenship” because they are perceived to be foreign and uncivilized. She explains:

Muslim Americans are in a position akin to the naturalized citizen, I mean they possess a citizenship that is always now at risk of being undone. Their identity as Muslims—in other words, “potential terrorists”—means that they are perennially suspected of having engaged in fraud or misrepresentation, with that fraud or misrepresentation consisting of a pretense of loyalty or allegiance to the United States .

Volpp 2583

As a nation, our essentialist view of Muslim Americans and Arab Americans generate assumptions that all Muslims and Arabs participate in terrorist activity. This presumption ultimately subjects the citizenship of Muslims and Arabs in the United States to constant inspection and examination. If any citizens suspect you of being disloyal to America, you can be deprived of your inalienable rights. Therefore, the precious citizenship of Muslim Americans and Arab Americans lies in the hands of private citizens as they are the ones who determine if they are worthy of claiming the American identity.

How do the private citizens of the United States regulate the citizenship of Muslim Americans and Arab Americans? Surveillance serves as a mechanism for the American public to micromanage the daily lives of Muslim Americans and Arab Americans, stripping them of their rights as citizens. There is no denying that a number of policies were passed and enforced by the federal government during the War on Terror that strengthened surveillance within the United States. Yet, it was the private American citizens who carried out the surveillance of Muslim Americans and Arab Americans on the microscopic level of everyday life. In her book Forever Suspect: Racialized Surveillance of Muslim Americans in the War on Terror, Selod uses the experience of a Pakistani woman named Maham to convey the hyper-surveillance of Muslim Americans and Arab Americans. Maham describes to Selod that the FBI showed up to her front door one day because “someone went out of their way to not only watch me at the post office, but basically got our license plate number, turned it into the police as someone suspicious mailing something, and then the police [were] able to track license and registration and find us” (Selod 96). In reality, Maham went to the post office to send clothes to her relatives in Pakistan (Selod 95). The experience of Maham reveals how Muslim Americans and Arab Americans cannot perform daily tasks without being watched over by their fellow citizens. Muslim Americans and Arab Americans have the eyes of the American public inspecting every aspect of their lives because they are suspected to be engaged with terrorist activities due to their religion or race.

This process of surveilling the lives of Muslims and Arabs in America coincides with Carlos Latuff’s 2011 political cartoon displayed on the left. The artist depicts a Muslim family with red targets on their backs which were drawn with a pen that consists of the burning Twin Towers (Latuff). The imagery of the cartoon represents how the events of 9/11 placed a metaphorical target on Muslims and Arabs all across the nation since the hijackers identified as Muslims and had Arab ethnicity.

The drawing of targets on the caricatures represents how as a nation, we have “othered” both Muslims and Arabs alike by enforcing a discriminatory system of surveillance that scrutinizes their lives. These people cannot escape the targets they have on their backs since they are being constantly watched over by the American public and presumed to be affiliated with terrorism.

The hyper-surveillance of Muslim Americans and Arab Americans inevitably excludes them from the most basic rights and privileges of citizenship. Both Moustafa Bayoumi, an English professor at the City University of New York, and Saher Selod portray how private citizens hinder Muslim Americans and Arab Americans from achieving the rights of citizenship. Bayoumi describes how racism causes people to define themselves against others ultimately leading to exploitation, extermination and exclusion (Bayoumi 270). When we hold an essentialist view of people different from us and subject them to the othering process, we feel that this foreign group is not worthy of obtaining the same rights and privileges as us. In order to maintain our sense of superiority, we do anything within our power to exclude these groups from specific rights and privileges. This is what the American public has done to Muslim Americans and Arab Americans in the Post-9/11 era. Ordinary citizens have surveilled Muslim Americans and Arab Americans closely to ensure that they remain in a state of inferiority. Saher Selod in her book describes that, “when private citizens participate in the hyper-surveillance of Muslim Americans, they create an environment of exclusion” (Selod 97). The surveillance of Muslim Americans and Arab Americans allows private citizens to inspect every single element of their daily lives. The works of both Bayoumi and Selod express how the climate of exclusion that surveillance creates, hinders Muslims’ and Arabs’ access to many of the basic rights of American citizenship on the basis of their race and religious preference.

Although it is our nation’s most prevalent right, Muslim Americans and Arab Americans are stripped of their freedom of speech since private citizens associate the Arabic language with terrorism. In a CNN News segment, Khairuldeen Makhzoomi, a student at the University of California Berkley, discusses with a reporter in a Skype interview how he was removed from his flight because he was speaking the Arabic language. Makhzoomi talks about the events that unfolded before and after he was kicked off the Southwest plane. He describes that when he was talking to his uncle, he said the Arabic phrase “In Sha Allah” (ان شاء الله in Arabic) which means, “God Willing” or hopefully (CNN). After he said this phrase, the woman sitting in front of him got up from her seat to notify airline security. Once told to get off the plane, Makhzoomi stresses how Southwest security, specifically the man who pulled him off the plane, “was a little bit disrespectful and he kept saying ‘look what you have done. The plane is now delayed 30 minutes because of you.’ I told him this is not me; this is what Islamophobia has got this country into. He told me, ‘You know what you are not going back to the plane.’ and the police officer reached to his device and said ‘Call the FBI! Call the FBI!’” (CNN). This interview with Khairuldeen Makhzoomi portrays the reality that since 9/11, the ordinary citizens of the United States of America have associated terrorism with Muslim and Arab identity. Here we see how just by saying the word “Allah,” Makhzoomi was deemed to be a terrorist by the passenger on the plane. I have been studying the Arabic language for over a year at the University of Oklahoma, an educational institution that is known nationally for its Arabic programs. According to my professor and my teaching assistants, there are hundreds of commonly used phrases and expressions that use the word “Allah” such as “In Sha Allah.” However, due to the fear of Islam and the common assumption that all Muslims and Arabs are terrorists, Muslim and Arab Americans cannot even speak their own language without receiving scorn from their fellow citizens. For Muslim Americans, simply saying “Allah” on a plane is similar to yelling “bomb.” Language is a key component of our lives as citizens. By vilifying the Arabic language, Muslim Americans and Arab Americans are unable to speak freely without receiving negative judgment and ridicule from their fellow citizens, literally hindering their right to free speech.

Along with the freedom of speech, Muslim Americans and Arab American’s freedom of expression is limited as private citizens use the hijab as a way to question the allegiance of Arab and Muslim women to the United States. The hijab is a common article of clothing worn by Muslim women for a variety of reasons. Some women believe that they are obligated to wear the hijab in order to please Allah. Others choose to wear the hijab because it is a way to express one’s Muslim identity. No matter what a woman’s reason is for wearing a hijab, the article of clothing possesses a religious and cultural significance to it, and is a common form of expression among Muslim and Arab women. However, following the events of 9/11, the hijab has turned into a symbol of foreignness amongst other private citizens. In her 2015 published journal article, Saher Selod discusses the patterns she discovered when hearing accounts of Muslim women after the terrorist attacks of 9/11. She explains how the American public has viewed the religious article of clothing as a symbol of “anti-American sentiments” ultimately putting Arab and Muslim women in a “precarious position of having to resist their exclusion from an American identity by defending the compatibility of their religion with American values” (Selod 84).

The hijab has become a mechanism that has subjected Muslim and Arab women to the racialization of Islam. Muslim women cannot dress the way they wish without receiving judgment from their fellow Americans. The essentialist view of the American public causes private citizens to use the hijab to identify people who are not truly faithful to America in their opinion. Since this article of clothing does not fit the traditional model of the American woman, they must then prove their allegiance and loyalty to their fellow American citizens. In addition, the racialization of the Islamic religion produced by private citizens has caused the hijab to have racial implications as well. When we see an Orthodox Christian woman wearing a head covering walking down the street, we do not rip the covering off from their head and yell at them saying “Go back to your county!” This example is where we see the racialization of Islam in full effect. The hijab has not only become a symbol of Muslim culture, but has served as a mechanism to subject American citizens with Middle Eastern and North African descent to bigotry. Muslim American and Arab American women’s freedom of expression has been limited in fear that they will be questioned and possibly excluded from claiming the American identity.

Not only does the racialization of the Islamic religion prohibit Muslim and Arab Americans from obtaining certain rights, but it also subjects them to verbal and physical abuse by private citizens. Both Selod and Considine express the hateful actions done to innocent Muslim Americans by their fellow citizens. In her book, Saher Selod interviews a Muslim woman named Nasreen who discusses an encounter with her neighbor following the attacks of September 11th, 2001. After she and her family stayed at home after the attacks, as all people did during the immediate aftermath, her neighbor came knocking on her front door shouting, “what are you doing in your basement. Are you making any bombs? Are you creating anything?” (Selod 90). Here we see how the fear from the attacks of 9/11 unfortunately caused Muslims to be presumed and identified as terrorists by private citizens. Nasreen’s experience reflects how 9/11 intensified Islamophobia within the United States. This fear inevitability caused private citizens to take extreme measures to uphold and enforce this racialization of Islam. In his journal article, Craig Considine utilizes the death of Cameron Mohammed to reveal the destructive effects of the racialization of Islam. When the killer of Mr. Mohammed was told by police that the man he killed was not Muslim, he replied, “they’re all the same” (Considine). The murder of Cameron Mohammed is one of the horrific byproducts of the racialization of Islam. Since Mohammed fit the public image of a Muslim, he was falsely associated with the Islamic religion ultimately leading to his murder. The real-life stories of the discriminatory actions directed toward Muslims and Arabs displayed in Selod and Considine’s work expose how the racialization process causes ordinary citizens to take various verbal and physical actions against Muslim and Arab Americans in order to maintain their status of superiority.

In order to defend their racist actions, private citizens argue that it is the government that is responsible for the racialization of Islam due to the passage of certain public policy provisions. As ordinary citizens, we tend to point fingers at our politicians and our governmental systems when it comes to issues of race. During the aftermath of the attacks of 9/11, Muslim and Arab Americans were targeted by public policy decisions due to the racialization of Islam. One of these policies passed during this era was the Special Registration program. This Department of Homeland Security program, “required all nonimmigrant males in the United States over the age of 16 who [were] citizens and nationals from select countries to be interviewed under oath, fingerprinted, and photographed by a Department of Justice official” (Bayoumi 271). These select countries primarily consisted of nations whose main religion practiced by its citizens was Islam. Here we see yet another example of Muslim Americans being unjustly targeted. While the government has played a role in the racialization of the Islamic religion, it is the ordinary citizens who are ultimately responsible as they influence the decisions political leaders make in office. As the War on Terror raged on in the coming years after 9/11, President George W. Bush and his administration wanted to back off on profiling procedures and practices, yet the American public thought otherwise. Hilal Elver explains in her academic essay that “Although the Bush Administration made clear that the government was keen to end racial profiling, the American public overwhelmingly accepted the racial profiling of Arabs, Muslims, and Middle Easterners” as public opinion polls during the Post-9/11 era “indicated that 60 percent of Americans favored ethnic profiling of Arabs or Muslims” (Elver 144). While our political leaders are the ones who physically sign public policy into effect, it is ultimately the voices and attitudes of the people that cause him or her to lift the pen.

My fellow Americans, we have allowed the actions of a few extremists to control our minds and inflict conflict and pain upon our fellow, innocent Muslim American and Arab American citizens. Even though this tragic event is approaching its 20th anniversary in approximately two years, Muslim Americans and Arab Americans are continuing to suffer at the hands of their fellow citizens as the Islamic religion is racialized and falsely interwoven with Arab ethnicity. We have created a society where Muslims and Arabs alike are perceived to be terrorists, and are treated as such. We cannot change these wrongdoings of the past, but we can take a stand and put an end to such destructive practices in the future. We must abandon our essentialist views of people who are genetically, culturally and religiously different from us. If we do not do this, how can we be a nation of equality and freedom? Our great nation was founded on the concept of egalitarianism (Allen). As citizens of the United States, we have the responsibility to uphold the foundational principle of equality for all. Through the racialization of Islam and the subjection of Muslim Americans and Arab Americans, it is evident that we have failed to fulfill our egalitarian commitment. We have a tendency to point fingers and blame our government officials for racializing the Islamic religion. However, if we look in the mirror, we will see that we, the private citizens of the United States, are to blame for the creation and enforcement of oppressive processes like racialization and essentialism. It is imperative that we take the time to get to know and embrace the characteristics of people different from us if we truly want to live up to our name as being a nation of all people, by all people, and for all people.

Works Cited

Adhami, Ridwan. “Islamophobia.” Found, Ridwan Adhami • Creative Director, 2010, www.ridwanadhami.com/#9.

Allen, Danielle S. Our Declaration: A Reading of the Declaration of Independence in Defense of Equality. Liveright Publishing Corporation, a Division of W. W. Norton & Company, 2014.

Bayoumi, Moustafa. “Racing Religion.” CR: The New Centennial Review, vol. 6, no. 2, As/Am: Declarations of Asian America, 1 Oct. 2006, pp. 267–293.

Byng, Michelle D. “Complex Inequalities The Case of Muslim Americans After 9/11.” American Behavioral Scientist, vol. 51, no. 5, 2008, pp. 659–674., doi:10.1177/0002764207307746.

CNN, director. 2:58 / 5:04 Arabic-Speaking Student Kicked off Flight. YouTube, YouTube, 18 Apr. 2016,www.youtube.com/watch?v=XGCZktZv3Bc.

Considine, Craig. “The Racialization of Islam in the United States: Islamophobia, Hate Crimes, and ‘Flying While Brown.’” Religions, vol. 8, no. 9, 2017, p. 165., doi:10.3390/rel8090165.

Elver, Hilal. “Racializing Islam before and After 9/11: From Melting Pot to Islamophobia .” Ten Years After 9/11: Rethinking Counterterrorism, vol. 21, 2012, pp. 119–178., doi:10.1093/acprof:oso/9780199769292.003.0008.

Latuff, Carlos. “Today Is 9-10-11 | #911 Attacks, 10 Years on #WTC ~ Cartoon by @CarlosLatuff.” Today Is 9-10-11 | #911 Attacks, 10 Years on #WTC ~ Cartoon by @CarlosLatuff, Occupied Palestine, 2011.

Lawrence, Bruce, editor. Messages to the World: The Statements of Osama Bin Laden. Verso, 2005.

“Oxford Dictionaries.” Oxford Dictionaries | English, Oxford Dictionaries, en.oxforddictionaries.com/.

Selod, Saher. “Citizenship Denied: The Racialization of Muslim American Men and Women Post-9/11.” Critical Sociology, vol. 41, no. 1, 2014, pp. 77–95., doi:10.1177/0896920513516022.,

Selod, Saher. Forever Suspect: Racialized Surveillance of Muslim Americans in the War on Terror. Rutgers University Press, 2018.

Volpp, Leti. “Citizenship Undone.” Fordham Law Review, vol. 75, May 2007, pp. 2579–2586.